Photo: Igor Vejnović (Bankwatch)

Author: Igor Vejnović, Hydropower Coordinator, CEE Bankwatch Network

Eight civil society organisations last week submitted proposals for a revamp of Serbia’s renewables support scheme to the Ministry of Energy and Mining.

All across Europe, renewables incentive schemes have been transformed in recent years to take account of the growing costs of feed-in tariffs for end consumers. Feed-in tariffs have proven effective at increasing the amount of renewable energy coming online, but as the installed capacity goes up, so do the costs.

In southeast Europe, incentives schemes have also attracted negative attention for their role in encouraging controversial small hydropower developments. The EU’s Energy and Environment Aid Guidelines, issued in 2014, aim to address such concerns by requiring competitive auctions to drive down the level of support required for each plant, as well as including sustainability requirements.

Serbia has been delaying the inevitable switch to these rules. Last year, the old Regulation on Incentive Measures that was about to expire was extended until the end of 2019. The Ministry announced that its first auction for solar and wind would happen in the second half of the year. This doesn’t look likely to happen as the needed regulations are still not in place, but as the old proverb says: “marry in haste, repent at leisure.” This delay may provide an opportunity for officials, experts, civil society organizations and renewable energy producers a chance to agree on which system would yield most benefits at the least economic and environmental cost.

Change needed to avoid a backlash against all renewables

Incentivising hydropower in Serbia and across the region has attracted investors, but the first come, first serve model of providing subsidies has led to chaos. Weak environmental governance means that the projects’ impacts often haven’t been assessed properly. Moreover, communities haven’t been consulted, violating their right to participation in environmental decision-making guaranteed by the Aarhus Convention. This has led to well-justified resistance against small hydropower plants.

Introducing a 500 kW limit for feed-in-tariffs as is currently required in the EU should serve to discourage some of the more amateurish investors we have seen building hydropower plants across the region. Still, additional efforts are also needed to bring even the smaller plants into compliance.

However, it’s not only about hydropower. Every technology can cause problems in the wrong place and if poorly planned, so for this reason we are also recommending that auction rules for renewable plants above 1 MW require bidders to obtain environmental and construction permits prior to participating in the auction. Given the need for improvements in the permitting system, which will take some time to be resolved, siting criteria for auctions also need to explicitly exclude ecologically sensitive areas or locations which may interfere with local people’s livelihoods.

We all want to increase the share of renewables in the energy mix. But this has to be done in a way that respects nature and local communities.

Give solar and wind a chance

Last week, as a first step to kick off a public dialogue on how to reform the incentives system, eight civic groups – CEE Bankwatch Network, the Centre for Ecology and Energy (CEKOR), the Rzav – God Save Rzav association, the Group for Analysis and Policy-making (GAJP), the Right to Water Initiative, the zajedničko.org Platform for theory and praxis on public goods, the Movement to Defend Stara Planina and WWF Adria sent a set of proposals to the Ministry of Energy and Mining.

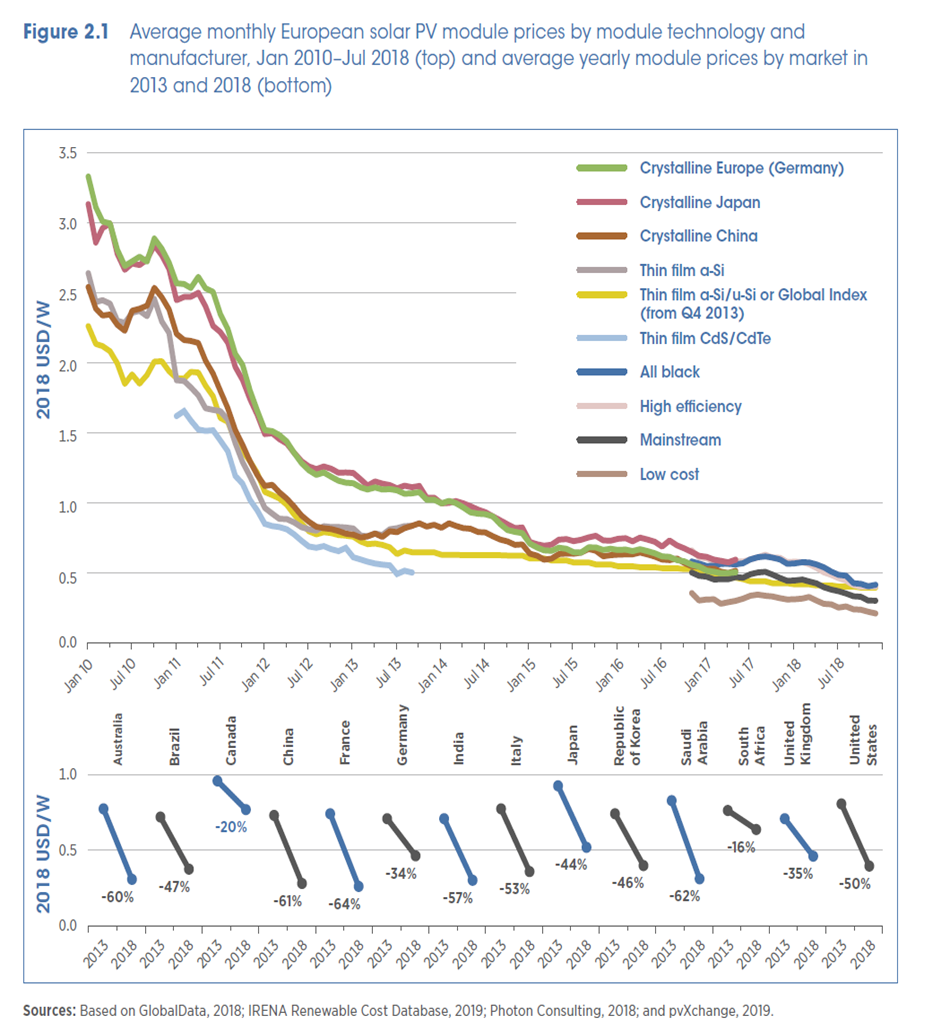

The groups are calling for a fair and effective system to promote newer technologies whose price is still falling, while phasing out subsidies for sources that show no sign of becoming competitive without support. IRENA’s recent report on the costs of renewables shows that the prices of wind and solar are still dropping while other technologies are stagnating. This means that supporting wind and solar is more cost effective in the long run because they should become competitive without incentives in the next few years.

Montenegro already has a 250 MW solar project in the pipeline for which no operating aid is expected, but for smaller projects we expect that support will still be needed for a while yet. Additionally, in 2015-2017 Serbia provided nearly four times as much support for coal as for renewables, so while coal subsidies are being phased out and CO2 payments phased in, renewable energy will still need a boost to be competitive.

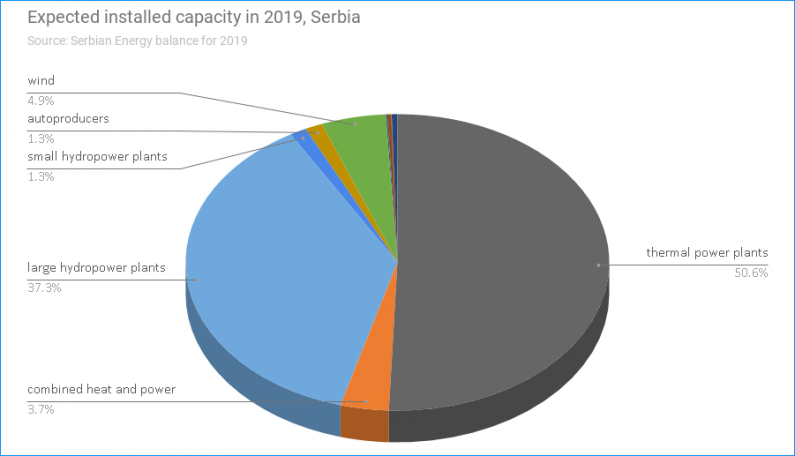

So far, Serbia’s renewable electricity generation capacity has been heavily dominated by hydropower. This year and next, its wind capacity should increase to 500 MW as several plants come online. Still, Serbia’s Regulation on Privileged Producers sets 500 MW as a cap until 2020 so no new projects have been able to enter the pipeline since early 2016. Solar PV is even less privileged, with a cap of 10 MW on incentivised installed capacity.

On the other hand, hydropower, geothermal, biomass and biogas have no such caps, giving them an unwarranted privilege, even though solar and wind have higher potential for additional capacity.

Yet solar energy is becoming ever-more important as it is resilient to climate change. As the European Environment Agency’s recent report shows, climate change is expected to reduce water availability in southern Europe – a phenomenon which is already affecting hydropower across the region.

Our vision: Real ownership of the energy transition

Another question is how to ensure that renewables incentives energy are available to ordinary people. Encouraging people to participate in generating their own electricity and heat is the way to create true ownership of the energy transition.

Rooftop solar, both photovoltaic and thermal, has massive unrealised potential in Serbia, although estimates vary widely on exactly how much could be installed. Serbia already has pioneers that are trying to develop solar projects. Ana Džokić from Belgrade has recently described her frustrating experience attempting to become a prosumer. She is currently wasting 77 percent of the electricity generated.

Although Serbia still needs to adopt legislation that regulates prosumers and net-metering it is also crucial that an accessible incentive system is in place that benefits ordinary households.

The way forward

Experience has shown that it is crucial to prevent resistance to renewables incentives by keeping their costs down and making sure they don’t finance controversial projects. But in order to build long-term support for energy transition, creating enabling conditions for community energy and prosumers is essential as well. In the coming months we will endeavour to ensure that both of these conditions are at the forefront of the planned incentives reforms in Serbia, to ensure the stable post-2020 framework we need.

Be the first one to comment on this article.