Photo: iStock

Packaging waste may not be the most common type of waste in Serbia in terms of amounts generated, but it certainly is the most widespread in places where waste shouldn’t be found: it’s scattered all over cities and towns, picnic areas, rivers and nature, with microplastics ending up in human bodies and even in babies’ placentas. The law says the responsibility and duty of care for packaging waste lies with those who place it on the market, namely businesses.

The existing waste collection and management model has failed to produce tangible results, except when it comes to paper and cardboard, and even metal packaging. Still, companies’ reports and marketing campaigns leave the impression that the situation is much better than it actually is. This doesn’t seem to bother anyone, so no new solutions are being pursued despite modest results.

Although there are fears, perhaps justified, that the state will yet again fail to do a job right in the waste management sector, no problems are expected with the planned deposit refund scheme, given that the model has so far proven very effective in almost every country that has implemented it.

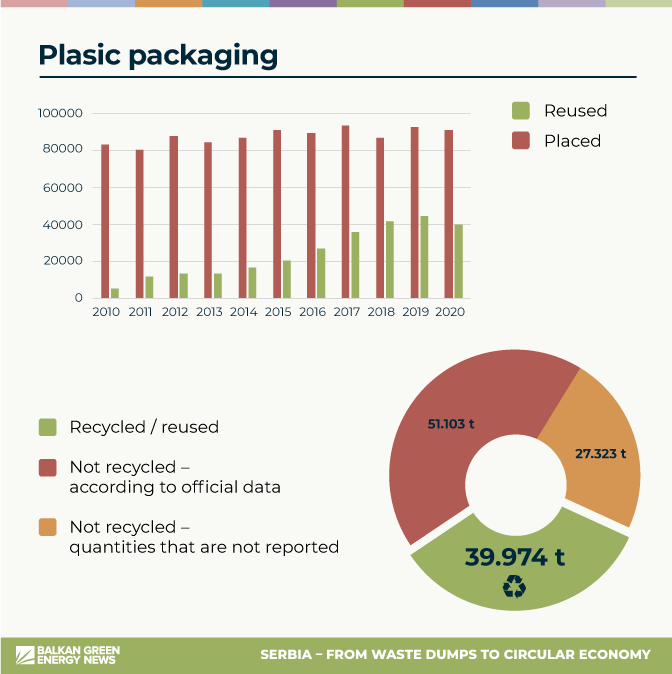

In the ten years since Serbia’s Law on packaging and packaging waste and the reporting requirements for businesses came into force, about 3.7 million tons of packaging waste has officially been placed on the market, of which 1.5 million tons, or 39%, was recycled, or reused, while some 2.2 million tons ended up uncontrolled in nature or in landfills.

About 30% of businesses in Serbia do not report correctly, or at all, to the Environmental Protection Agency

In reality, the figures are different as it is estimated that about 30% of businesses in Serbia fail to report correctly, or at all, to the Environmental Protection Agency. On top of this, companies that place on the market less than one ton of packaging waste a year are exempt from the reporting requirements. This means that the official data should be taken with a pinch of salt until order is brought into the packaging waste management and reporting system.

Also, one look around is enough to see that waste is all over the place, defacing and causing permanent damage to nature, as well as humans. It is therefore clear that companies’ marketing success stories are misleading and that the hard work is still ahead.

In this latest article in the series “Serbia, from garbage dumps to circular economy,” we discuss the functioning of the country’s packaging waste management system and ways to improve it with Violeta Belanović Kokir, general manager of packaging waste management system operator Sekopak, Kristina Cvejanov, a packaging waste expert, and Dragana Katić, an environmental activist and founder of the Trash Hero movement in Serbia.

Experts for packaging waste we spoke with: Kristina Cvejanov, Dragana Katić, Violeta Belanović Kokir

Ten years of packaging waste management – a 39% success rate

Under Serbian law, producers – companies that place packaged products on the market- are responsible for packaging waste. They have the obligation to incorporate the cost of separate collection of their packaging waste into the price paid by final consumers, and to use the funds to ensure their packaging ends up in waste recycling facilities instead of landfills or nature.

39% of packaging waste placed on the market in the last ten years was managed

Under the extended producer responsibility system, implemented in Serbia over the past 11 years, companies have ensured the collection of 1.5 million tons of their packaging waste through operators of the system. Most of the waste was collected from companies themselves. Although the amount was enough for businesses to meet the target set by the government, it represents only 39% of all packaging waste placed on the market, while the remaining 61% was left unmanaged, landfilled, or dumped in nature. In terms of the impact of packaging waste on the environment and human health, this rate is not enough.

One of the reasons for this underperformance is the fact that the bulk of household packaging waste – cardboard boxes, wrapping paper, plastic bottles, containers and cling film, cans and tins, glass bottles and jars – still ends up in landfills even though almost all of it can be used as a resource to manufacture new products or generate energy.

Belanović Kokir: packaging waste system operators provide a direct link between producers and collectors

Violeta Belanović Kokir, general manager of Sekopak, Serbia’s first and biggest system operator, is very satisfied with the results achieved so far. She says that system operators provide a direct link between producers and packaging waste collectors. The idea of a “joint” company was born out of the need to establish an efficient and sustainable packaging waste management system, and this model has proved to be the most effective one so far, according to Belanović Kokir.

Funds from environmental fees in Serbia are misused

The alternative to this system, according to her, is for businesses to pay a packaging fee to a state-controlled fund, which would then invest in waste collection infrastructure and help cover the costs of collectors and utility companies. In Serbia, this would be problematic having in mind that funds collected through the existing environmental fees are misused, and that the practice was “legalized” in the 2015 Budget Law in contravention of European Union (EU) regulations.

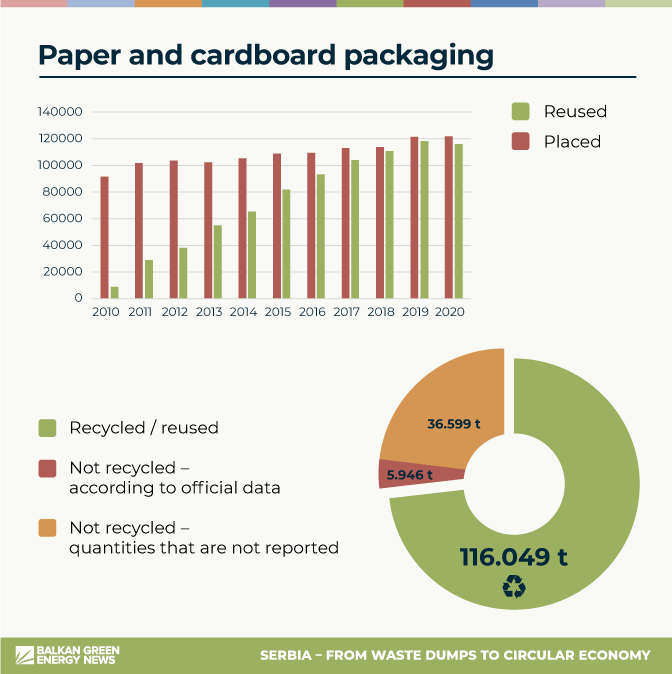

The best result in packaging waste management, of 95%, was achieved in the paper and cardboard packaging industry

The paper and cardboard packaging waste management system in Serbia is functioning well, as evidenced in the Environmental Protection Agency’s report for 2020. It shows that as much as 116,049 tons, or 95%, of cardboard packaging was recycled, mostly commercial packaging collected at retail shops and factories.

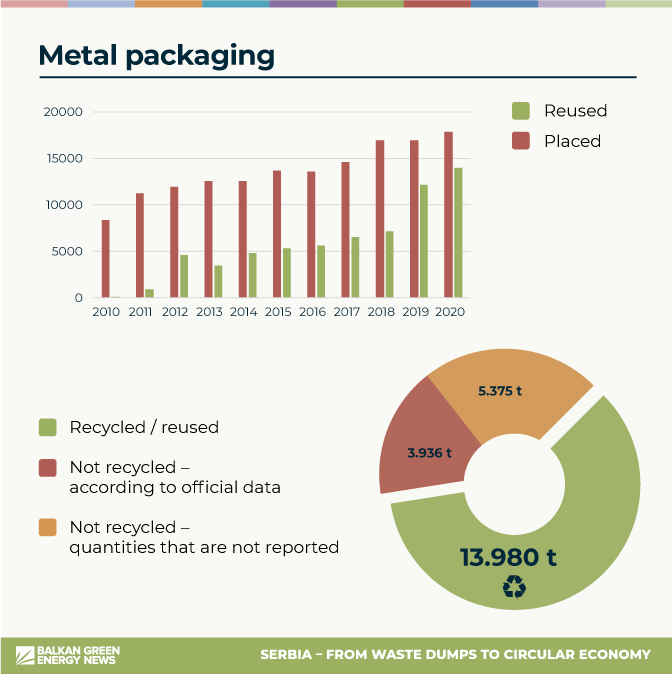

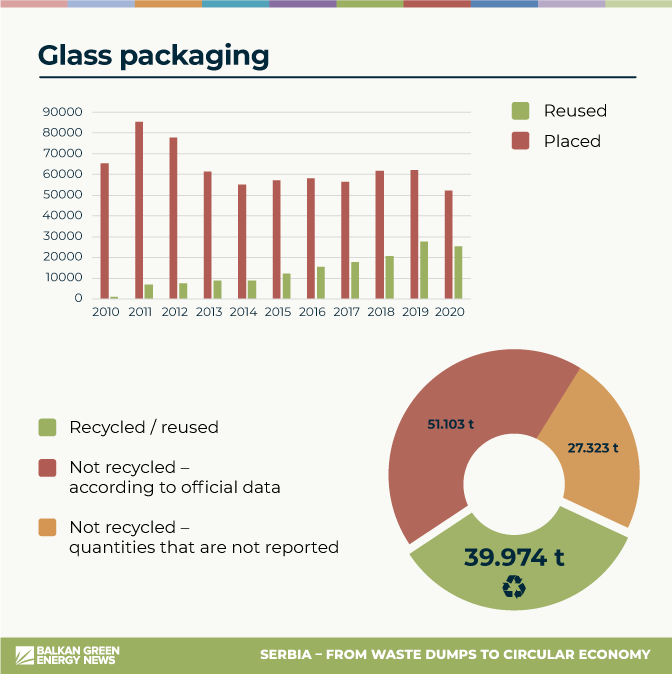

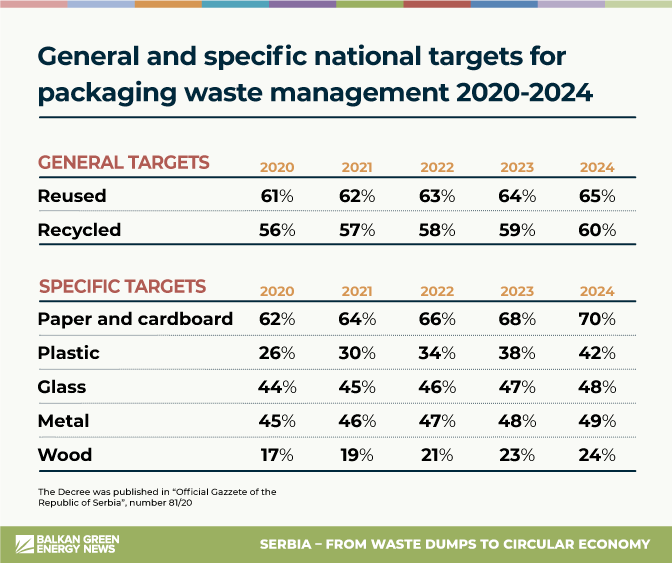

Metal packaging had a 78% recycling rate, followed by glass, with 48%, wood, 40%, and plastic packaging, 34%

According to the same report, the next highest recycling rate, of 78% (13.980 t), was seen in the metal packaging segment. Recycling rates of below 50% were recorded in the glass, wood, and plastics segments – 48% (25.155 t) for glass, 40% (30.723 t) for wood, and 34% (39.974 t) for plastic packaging.

However, if Serbia tightened inspection oversight and control, and compelled companies to report the full amounts they place on the market (which they don’t, however incredible that may sound), the recycling rates would decline significantly, giving us a better picture of the actual situation – instead of collecting packaging waste and using it as a resource, we pollute nature by dumping some 300,000 tons of it into the environment.

After opening Chapter 27 of its EU accession talks, Serbia has stepped up activities to harmonize its regulations EU directives. This means that regulating the work of operators and establishing a so-called clearing house have become relevant and necessary goals. “Introducing these two instruments would certainly improve the efficiency and transparency of the existing system,” says Belanović Kokir.

The role of clearing houses in EU member states is to oversee the amounts of packaging that businesses place the market, partially taking over the authorities of inspectorates, which do not have the capacities to control all those required to pay the packaging fee.

By implementing this mechanism, Serbia would ensure more accurate reporting to the Agency for Environmental Protection, and consequently to citizens, who pay for the cost of waste management through prices of goods and services they buy. It would also ensure higher collection rates for the packaging fee, and enable more investment in the collection of this type of waste.

In addition, to ensure the packaging waste management system is fully functional, it is necessary to introduce a fee (charge) on waste that ends up in unsanitary or sanitary landfills, or in the environment. This means that companies placing packaging on the market should pay a fee on everything that is not recycled or reused.

The charge would also encourage producers to change the design of non-recyclable packaging (e.g. aluminum-laminated plastic packaging for snacks and biscuits) as well as to invest in a system for the collection of recyclable waste that is currently not recycled, such as plastic bags. Solutions and technologies exist, and there is no justification for failing to improve the situation.

The charge would bring in considerable revenues. The charts show that the amounts of uncollected waste (whether reported or not reported) are still large. The data from the charts corresponds entirely with the scenes that Serbian citizens, without any inspection reports, can see for themselves in cities, villages, and nature.

“Biodegradable” plastic bags – a costly delusion

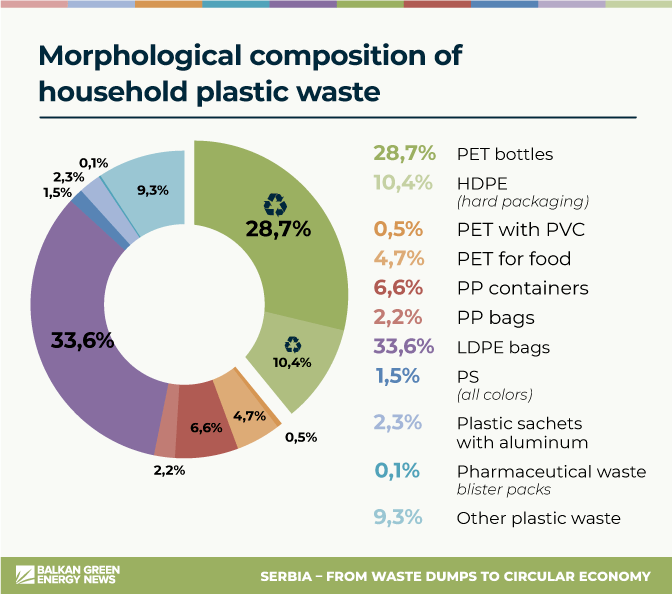

Separating plastic bags from communal waste is extremely expensive and demanding, and is not possible without using state-of-the-art technologies at waste separators and without paying waste sorting fees to utility companies. Even though retailers in Serbia charge customers for plastic bags, and even though financial mechanisms are in place, the revenues are not invested in waste collection and recycling.

Serbia’s law encourages the use of oxo-degradable bags, which are falsely marketed as biodegradable

Plastic bags are disposed of at landfills. To make matters even worse, Serbia has adopted a law that encourages the use of oxo-degradable bags, which are misrepresented in public as biodegradable. These bags are in fact conventional plastic bags with additives that facilitate their fragmentation into tiny pieces. These tiny fragments, called microplastics, do not simply vanish, but they rather reach the soil, air, water, and even the food chain, much faster than regular plastic bags, according to Kristina Cvejanov, a packaging waste expert.

The EU banned oxo-degradable bags in July 2021

The presence of microplastics has been determined in various human organs, including the fetal placenta. This is why oxo-degradable bags are banned in the EU from July 3, 2021. Serbia, on the other hand, incentivizes them as an ecological solution by exempting their producers from the environmental fee, which costs the state budget about EUR 1 million annually, according to Cvejanov. That money could be used to finance the separation of plastic bags from communal waste and recycling, she says.

The new “ecological” bags bring profits to producers and retailers, while the cost is shouldered by consumers

Even though Serbia has introduced the obligation to charge for plastic bags, the revenues are not used for addressing the pollution they cause. That means lower costs for producers and higher revenues for retailers, leaving citizens with the environment polluted by microplastics, according to Cvejanov.

In the existing circumstances, there is no financial incentive for utility companies, including regional landfills with waste separation facilities, to separate plastic bags or for recyclers to build processing facilities, she explains. Serbia should promptly ban oxo-degradable bags, as the EU has done, and use the environmental fee revenues to subsidize utility companies and help cover the costs of the collection, separation, transportation, and treatment of plastic bags, according to her.

With the new “ecological” bags, Serbia has legalized something that is contrary to common sense without anyone even noticing

Worryingly, it seems that even though producers are formally responsible, these bags are in fact nobody’s concern. The state has legalized something that is contrary to common sense without anyone even noticing. Nobody is even asking who profits from plastic bags or why there is no money for their collection, says Cvejanov.

Waste collection and recycling are not profitable activities on their own, and financial mechanisms are needed to incentivize reuse, she explains.

The environment in Serbia is polluted and recycling rates are low because nobody understands the economics of waste, according to her. “Nobody in Serbia is dealing with this issue strategically. Neither do the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the Ministry of Finance understand the significance of these mechanisms. If that weren’t the case, we wouldn’t have plastic bags in tree tops and rivers,” says Cvejanov.

EU packaging waste recycling targets are unachievable without a better collection system

The Law on packaging and packaging waste assigns the responsibility for packaging waste management to businesses placing packaged products on the market, and these companies have passed on the responsibility to packaging waste system operators. Serbia currently has seven such operators (Sekopak, Delta Pak, Ekostar Pak, Ekopak sistem, Ceneks, Tehno Eko Pak, and Uni Eko Pak).

Operators cannot establish an efficient packaging waste management system on their own

The results achieved in the past ten years show that operators do not have the capacity to establish an efficient packaging waste management system on their own, and that it requires synergy, responsibility, and the engagement of relevant ministries and inspectorates, local authorities, utilities, and citizens themselves.

The three experts who spoke for Balkan Green Energy News believe that Serbia will not be able to meet the EU’s ambitious packaging waste recycling targets unless it improves its regulatory framework, brings order into its waste management system and economics, and enable the development of efficient, market-based recycling that involves profitability for waste collecting utilities, whether public or privately owned.

Talking about the roles of the state and local authorities in the implementation of the Law on packaging and packaging waste, Belanović Kokir says that the law defined the obligation of industry, but not the specific obligations of local governments. On the question of how businesses can help use packaging waste as a resource, instead of it ending up in landfills, the general manager of Sekopak says that companies placing packaged products on the market have the obligation to meet the national recycling and reuse target, which is set at 63% for this year.

Ten years on, it is obvious that the failure to define the specific obligations and recycling targets for local authorities was a major omission in the law, given that the collection of communal packaging waste is not possible without the engagement of local authorities. And, in turn, without source separation of packaging waste, which makes up over 20% of the volume of waste in landfills, a very important resource remains untapped, says Belanović Kokir.

Prices of packaging include production costs, but not its adverse environmental impact

Dragana Katić, an environmental activist and founder of the Trash Hero movement in Serbia, says that packaging waste accounts for about a half of the waste collected in cleaning operations in urban areas. The bulk of that packaging waste is made up of single-use plastic bottles, caps, bags, and cellophane wrapping for snacks and sweets.

Single-use packaging, according to her, poses the biggest problem due to its mass production, short-term and widespread use, and low price. Prices of packaging include the costs of production, but not its adverse environmental impact or the cost of collection, transportation, and potential recycling.

Producers should pay higher environmental fees if their products or packaging cannot be recycled, which would give them a financial incentive to consider eco-design. The state could then invest those funds in the collection and reuse of that waste to generate energy, or in improving environmental standards at landfills in order to prevent harmful substances from reaching the environment, according to Katić.

On the other hand, a deposit refund system, where the consumer pays for packaging in advance and gets a refund after returning it, is not yet functioning in Serbia, so citizens are not motivated to keep product packaging.

Neither the consumer nor the producer is responsible for packaging waste

“There is no deposit requirement that would make consumers responsible for taking care of their waste, nor is there any obligation for the producer to collect packaging waste – charges for producers are so low that we can by no means talk about their responsibility for the packaging they make,” she says.

In their marketing campaigns, producers are always casually providing data on the percentage of recyclable packaging, but never the amounts that will actually be collected and recycled, according to her. People in so-called developed countries, according to Katić, are neither more environmentally conscious nor more intelligent than people in Serbia, but laws in those countries are respected because fines for the irresponsible treatment of waste are very high, while responsible behavior is encouraged and rewarded.

Breaking the Law on waste management (photo Kristina Cvejanov) – Even though it is prohibited to dump packaging waste from retail shops and other businesses into communal waste bins, such practices are rarely penalized. Businesses are required to hand over their waste to authorized collection operators so it can be managed in line with the Law.

Solutions: financial responsibility for companies and financial incentives for individuals

Trash Hero Srbija is a member of the global movement Break Free From Plastic, fighting to reduce plastic waste. Katić believes that shifting the narrative which puts all responsibility on individuals is key to the success of that fight.

Katić: any individual effort to sort and recycle plastic waste is rendered futile by the fact that hundreds of thousands of plastic bottles are manufactured each second

Any individual effort to sort and recycle plastic waste is rendered futile by the fact that hundreds of thousands of plastic bottles are manufactured each second, she says.

Katić explains that the extended producer responsibility concept requires plastic producers and trademark holders to collect and take back their waste instead of shifting the responsibility to consumers and costs to local authorities.

According to estimates, raising the prices of products in plastic packaging by just RSD 1 per unit would ensure millions of euros needed for the development of waste collection and treatment infrastructure. The packaging fee for a product in a PET bottle currently stands at about RSD 0.02, while the fee for a product in aluminum-laminated plastic sachet is a negligible RSD 0.002.

The solution to this crisis would be for businesses to fully cover the real costs of plastic pollution. Instead of misleading marketing campaigns, the solution is in imposing the obligation to collect packaging waste, introducing policies aimed at increasing reuse, rolling out a refill and return system, and phasing out the problematic categories of single-use plastics.

The experts’ ten recommendations for improving packaging waste management in Serbia

- To achieve the EU’s recycling goals as early as 2025, as envisaged by the Ministry of Environmental Protection in its waste management program, Serbia needs a radical shift and swift change in its packaging waste management system.

- Introducing a charge on landfilled packaging waste in order to make landfilling the most expensive option for businesses.

- Implementing eco-modulation – the packaging fee should be higher for packaging that cannot be recycled or reused.

- Ensuring that revenues from the fees are spent for the right purposes –investments in infrastructure and in packaging waste collection and treatment.

- Introducing a deposit refund scheme for packaging, which would enable the collection of over 90% of beverage packaging – PET and glass bottles, cans, and cartons, which are 100% recyclable.

- Prohibiting oxo-degradable bags in order to reduce the microplastic pollution of soil, water, and air and ensure funds needed for its separation from communal waste and recycling.

- Prescribing recycling targets for local authorities, which would split the responsibility between the business and the public sectors, while providing an incentive for local authorities to work on improving the capacities of their utility enterprises.

- Introducing a clearing house to enable better supervision over the packaging waste market. The clearing house would audit data on the amounts of packaging that businesses place on the market and the amounts they report to the Agency, for which they pay a fee to system operators. This would help increase revenues and, consequently, investments in the packaging waste management system.

- Improving the packaging registry at the Agency for Environmental Protection in order to improve the quality of data, enable a more accurate insight into the situation, and provide a realistic basis for planning the investments needed to meet the recycling targets Serbia sets in line with EU regulations.

- Switching to the “pay as you throw” model and introducing an additional, “recyclable” trash bin for households to enable financial incentives for citizens who sort their waste.

- A major obstacle to the development of waste collection infrastructure is the lack of locations for the construction of recycling yards and deploying communal bins and recycling points. It should be mandated by law that local waste management plans are harmonized with local spatial plans to ensure that local spatial plans clearly allocate locations necessary for a successful implementation of local waste management plans.

GOOD TO KNOW

PRIMARY PACKAGING – the smallest unit of packaging in which products are sold to the final consumer (e.g. jars, cans, plastic bottles).

SECONDARY PACKAGING – a grouping of a certain number of sales units in primary packaging intended for sale to final consumers at the point of purchase (e.g. cardboard boxes with products in primary packaging, plastic bottles wrapped in cling film).

TERTIARY (TRANSPORT) PACKAGING – intended for the safe transport and handling of products in primary or secondary packaging (e.g. pallets).

SINGLE-USE PACKAGING – intended to only be used once.

RETURNABLE PACKAGING – packaging that can be refilled or reused for the same purpose after being returned by the final consumer.

DURABLE PACKAGING – packaging with the average lifespan of five years or more.

EXTENDED PRODUCER RESPONSIBILITY – a concept where those who produce or place on the market a product or packaging are responsible for it during its entire lifecycle. The responsibility involves applying eco-design, organizing the collection of waste packaging or products, and covering the full cost of its disposal to prevent it from ending up in the environment.

PRIMARY SEPARATION OF WASTE – waste sorting at the source (households, businesses, recycling points…). Waste is separated into special receptacles and then transported for further processing (secondary separation etc.)

SEKUNDARNA SEPARACIJA OTPADA –the separation of waste at automated lines, operated by waste management enterprises, into fractions that can be reused either for recycling or for energy production and/or fractions that have to be landfilled.

COMPOSITE PACKAGING –packaging made up of different materials (various types of plastics, aluminum, paper) integrated into a composite which cannot be separated by hand.

GENERAL PACKAGING WASTE REDUCTION TARGETS – ciljevi za ponovno iskorišćenje i reciklažu.

SPECIFIC PACKAGING WASTE RECYCLING TARGETS – targets for cardboard/paper, plastic, glass, metal, and wood packaging.

Be the first one to comment on this article.