Photo: thermal power plant Kolubara B (EPS)

Serbia’s decision to halt the construction of thermal power plant Kolubara B is the country’s first serious step in the energy transition. The move, however, does not mean that coal-fired power plants and mines will be closed down overnight, but rather marks the beginning of a process that will take decades. If the transition is prepared and carried out prudently, it will result in a cleaner environment and cheaper energy. However, if this is not done in a timely manner, the transition will be painful, first and foremost for those employed in the coal sector, but also for all citizens and the economy as a whole.

The suspension of all activities on the construction of Kolubara B, ordered by the Ministry of Mining and Energy, has sparked a heated public debate, which, unfortunately, has not been based in facts. Apart from obfuscating the latest development in the short-term, such uninformed debates could also have long-term consequences, such as the public’s misunderstanding of the energy transition process and lack of support for the changes that lie ahead.

Despite arguments to the contrary, Serbia can’t escape the energy transition, but this does not mean closing thermal power plants right away and laying off tens of thousands of workers, as has been tendentiously represented by its opponents. Rather, it means that the thermal power plants will be closed down over several decades, which would be their fate anyway given the approaching end of their operating life. The energy transition also means switching to cleaner and cheaper energy sources in order to mitigate the impact of emissions of CO2 and other harmful gases on climate change and human health.

Even without the energy transition, the thermal power plants have to be closed as their lifespan ends

Switching to cleaner energy means developing hydro, solar, and wind power plants to replace power and heating plants which burn coal, natural gas, and fuel oil, emitting sulfur-dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter (PM) and causing as many as 7,000 premature deaths in Serbia each year.

Renewable energy has also become a cheaper option given that energy produced from coal is already more expensive when the human and environmental cost is taken into account, while the price goes through the roof when the cost of carbon taxes is factored in.

Serbia has enough potential to produce its own clean energy

Finally, Serbia would not have to import clean energy since it has plenty of its own hydropower, wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass potential.

In order to devise a smart energy transition strategy, Serbia must understand what this change means and what developed countries, as well as those in the region, are planning, and define its goals. First and foremost, Serbia has to prepare for a coal phaseout, the most painful part of the energy transition for countries highly dependent on fossil fuels. This primarily means building new capacities and securing new jobs for workers that will be made redundant.

Completing Kolubara B simply isn’t commercially viable

Nikola Rajaković, a professor at the University of Belgrade School of Electrical Engineering (ETF), has told Balkan Green Energy News that at current prices, the owner of Kolubara B would generate annual electricity sales revenues of about EUR 100 million, the same amount it would have to pay in carbon taxes, while it remains unclear how the power plant would cover the costs of coal, labor, taxes and other expenditures.

The cost of carbon tax would be equal to the sales revenue from the entire output of Kolubara B

Since the introduction of a carbon tax in Serbia in only a matter of time, the logical conclusion is that this project is not economically viable, Rajaković explained.

Even if the carbon tax is disregarded, the price of electricity production, with all external costs – those incurred by the power plant and paid by citizens, such as healthcare, shorter life expectancy, reduced work ability, as well as air, water, and soil pollution – is markedly higher than the average wholesale prices on power exchanges.

Rajaković: Serbia must build solar and wind power plants, not thermal power stations, to replace existing coal-fired capacities

Renewable energy sources should not be idealized, but amid the urgent need for the energy sector decarbonization and climate change mitigation, the only conclusion that can be drawn from a comparison between green kilowatt-hours and those generated at Kolubara B is this: the government and state power utility Elektroprivreda Srbije (EPS) must build solar and wind power plants, not thermal power stations, to replace existing coal-fired capacities, according to Rajaković.

The levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for solar power plants in Serbia has been estimated at under EUR 40 per MWh, compared with at least EUR 80 per MWh for new coal-fired plants.

The problem with all Serbian thermal power stations is their age, with most of them operating since the 1970s. The youngest one is Kostolac B2, which has been online since 1987. Normally, their lifespan is 30 years, but it gets extended through overhauls. Even so, they can hardly operate for more than 50 years, which means that most of the thermal power stations in Serbia must be shut down by 2030 regardless of climate change, CO2, and international obligations. And, again, the construction of solar plants and wind farms is more cost-effective.

Miroslav Vujnović, a financial consultant with expertise in the energy sector, says that important factors to be taken into account when deliberating the Kolubara B project are emission prices, the so-called sunk cost, and the discount rate.

The prices of emissions set by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) for its projects in 2022 is EUR 56.29 per ton for CO2, EUR 8,313 per ton for SO2, EUR 8,010 per ton for NOx, EUR 28,732 per ton for PM2.5, and EUR 18,008 per ton for PM10.

The Kolubara B project has so far soaked EUR 100 million

According to a recent research, a 100 MW coal-fired boiler facility releases greenhouse gases (GHG) worth EUR 12.4 million a year. This translates into EUR 43.4 million a year for Kolubara B’s projected capacity of 350 MW. The costs of GHG emission are five times as high as labor costs, and are projected to rise at an annual rate of 2.257% in real terms. Moreover, these costs are not final, given that they mainly reflect the impact on air quality, without assessing other external costs (water pollution, noise, landscape degradation, the loss of biodiversity, etc.), according to Vujnović.

When it comes to sunk cost, an amount that has already been spent and cannot be recovered in the future, abandoning the construction of Kolubara B is not the first expenditure of this kind for Serbia, but it is the highest so far (the project has cost EUR 100 million so far). If we take into account all coal-fired power plants in the country, the figure is several billion euros, plus the costs of land reclamation and social welfare expenditures for job losses.

As for the discount rate, it increases dramatically when there is a clear time frame for a power plant’s shutdown, in this case 2050, which means that it is unlikely a project could have a positive net present value.

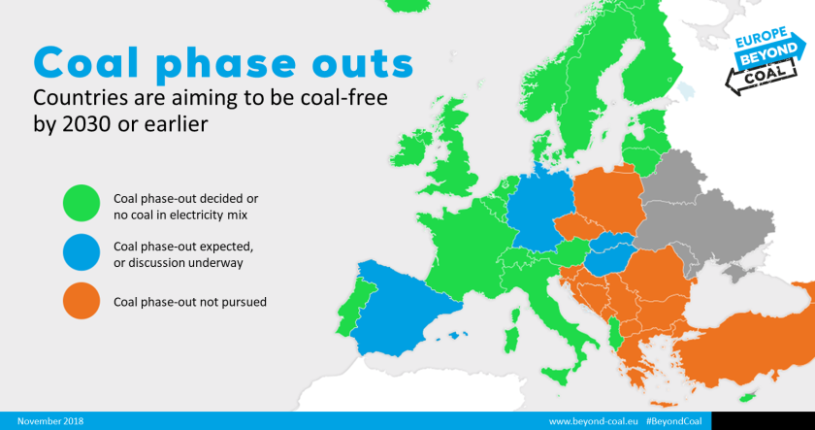

Large parts of the world plan to be coal-free by 2050

Coal phaseout plans in Europe (Photo: Beyond Coal)

The European Green Deal envisages the EU to be climate neutral by 2050, the same target set by Japan, while China hopes to reach climate neutrality by 2060.

Countries trading with the EU will hardly be able to operate coal-fired power plants after 2050

By 2050, countries whose foreign trade is dependent on the EU or the US, such as Serbia, will either have no coal-fired power plants or pay for their operation dearly. The EU has recently agreed on a climate law that will make climate neutrality by 2050 a legally binding target for all member states. Even before this decision, as many as 20 out of the 27 EU members had set a date for abandoning coal.

Countries outside the EU, such as the United Kingdom, are also working on decarbonization, and will not allow their economies to become uncompetitive. For example, steel mills from Serbia or China will not be allowed to sell their products in the EU cheaper than their European competitors just because they are not subject to a carbon tax. For this reason, the EU is introducing a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which will impose a tax on goods imported from countries that do not have a tax on CO2 emissions. A proposal of this regulation is expected in the coming weeks.

This levy would make Serbian exporters to the EU less competitive. It remains to be seen, however, whether the EU will impose the tax on all exporters from Serbia and other countries or whether it will grant a privileged status to those consuming green energy.

The costs of electricity generation at solar power plants have decreased by an average of 18% a year since 2010

In parallel with the process of the adoption of climate and energy regulations, the world has seen a “technological revolution” reflected in decreasing costs of electricity generation at solar power plants and wind farms. The costs of electricity generation at solar power plants have fallen by an average of 18% a year since 2010.

The construction of solar power plants and wind farms is still being subsidized, but there are more and more projects which do not need such support and which are financed through corporate power purchase agreements (PPAs) or which need very small amounts of state aid, mainly as a guarantee for their creditors.

Region taking first but bold steps towards decarbonization

A wind farm on coal pits – a sight from the EU that is slowly emerging in the region as well (Photo: Herbert Aust from Pixabay)

And what is going on in the region? It is of note that two out of the three EU member states from the region have not yet announced the year when they plan to become coal-free: Bulgaria and Croatia. As for the rest of the region, the situation is somewhat more straightforward in North Macedonia, which is using its last remaining coal reserves and is considering phasing it out by 2030, while Montenegro has announced it will set a coal phaseout deadline in its national energy and climate plan (NECP).

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, one thermal power station (unit 7 at TPP Tuzla) is being built in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH), while the country’s other political entity, the Republic of Srpska, has no such plans. Montenegro intends to carry out an environmental overhaul of TPP Pljevlja, while investors have dropped plans to build a coal-fired plant in Kosovo*, although the authorities have not yet made a final decision on abandoning the project. Serbia, for its part, is building Kostolac B3, with an installed capacity of 350 MW.

Only two thermal power plants are being built in the region, with North Macedonia and Montenegro on track to set coal phaseout deadlines

Power utilities in non-EU countries in the region, too, are aware that before too long they will have to pay some kind of CO2 emissions tax. For this reason, EPBiH and ESM have decided to introduce internal carbon pricing in their financial reports.

The price of CO2 emissions in the EU has soared by a staggering 140% in the past year, to an all-time high of EUR 55 per ton. This could push Slovenia’s thermal power plant Šoštanj some EUR 150 million into the red this year, while EPBiH has said it would have to pay EUR 200 million in carbon tax a year, making its thermal power plants unprofitable. This also involves costs that could spill over to all taxpayers, given that the power utilities are state owned enterprises. The state, or rather, citizens, would have to set aside hundreds of millions of euros to keep these enterprises afloat.

How it all began: the minister’s letter to the general manager

Milorad Grčić and Zorana Mihajlović at Kostolac B3 construction site (Photo: EPS)

A row between the Ministry of Mining of Energy on the one side and EPS and the Kolubara mining basin trade union on the other began after Minister Zorana Mihajlović sent a letter to EPS General Manager Milorad Grčić, informing him that it would not be possible to continue with the construction of Kolubara B.

The reason for such a decision, according to the letter, is the fact that Serbia has committed to aligning its energy policy with the EU and that it has signed the Sofia Declaration in which it agreed to work towards the 2050 target of a carbon-neutral continent together with the EU. This means that lignite must be replaced with natural gas and renewable energy sources, according to the ministry.

The letter was sent as part of the ministry’s work on drafting Serbia’s national energy and climate plan (NECP).

The union and EPS believes that Serbia is faced with the closure of thermal power plants and sizeable electricity imports

The miners’ union responded furiously, accusing the minister of planning to shut down the thermal power plants and mines overnight and of supporting the electricity import lobby. In a letter to the media, Miodrag Ranković, the union’s president, described the NECP as a “strategy to close the thermal power plants in Serbia from 2021 to 2030.”

Grčić sided with the miners, recalling that the previous ministry supported the Kolubara B project.

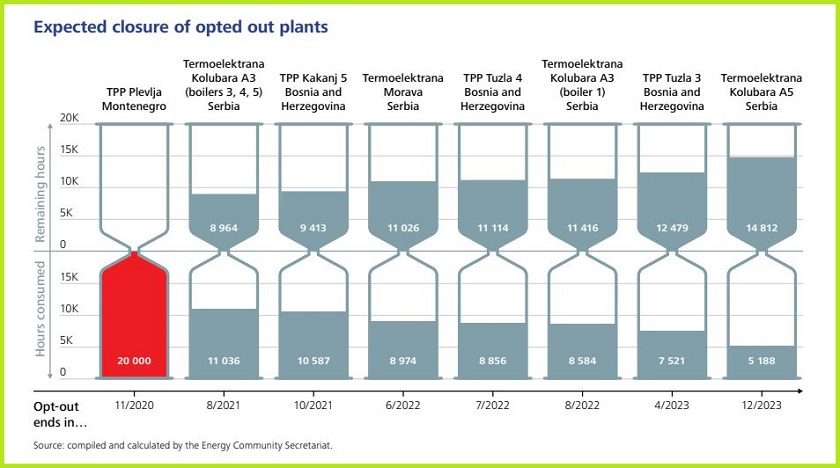

EPS is set to lose 600 MW of generation capacity, but 500 MW of wind farms have already been built in Serbia, with a further 1 GW likely to be online in five years

Grčić said it is important to complete Kolubara B, whose projected capacity is 350 MW, because EPS will soon lose 600 MW of its generation capacity, including two facilities with a total capacity of 324 MW – TPP Kolubara A and TPP Morava – which are planned to be closed by the the end of 2023.

Expected closure dates of 10 units at thermal power plants in the region (Photo: Energy Community)

On the other hand, EPS is building TPP Kostolac B3, with a capacity of 350 MW, while TPP Kolubara A and TPP Morava have been operating below capacity for years. EPS is also developing a 66 MW wind farm, although the project has been ongoing for nearly ten years, and it has announced plans to install solar power plants with a total capacity of 130 MW.

Over the past several years, foreign companies have built a total of 500 MW of wind power capacities in Serbia, while a further 1 GW could be built over the next five years. Earlier this year, it was announced that wind projects totaling 2 GW are under development. Combined with solar power plants and projects in early stages of development, the figure will reach almost 4 GW.

Rajaković: the energy transition is an opportunity for Serbia

TPP Kostolac B is EPS’ youngest thermal power plant, put in operation in the late 1980s (Photo: EPS)

Professor Nikola Rajaković says that halting the Kolubara B project is undoubtedly the first serious step in Serbia’s energy transition, but that it by no means implies an immediate shutdown of thermal power plants.

The new unit under construction at Kostolac will most likely be the last to be closed, probably around 2045, but the others must be decommissioned earlier as their lifespan is set to expire, according to him. The transition will most certainly last more than 20 years, according to him.

Rajaković sees the energy transition generating much more jobs than business as usual in Serbia’s energy sector

It is not true, according to Rajaković, that abandoning the Kolubara B project and closing thermal power plants will result in increased electricity imports, because the thermal plants will only be shut down once enough wind and solar capacities have been built. Rajaković also said that sees much more jobs in a future defined by the energy transition than in the existing situation in Serbia’s energy sector, especially in the digitalization and software segment.

“It seems like the winning combination for Serbia, but it needs to be accepted and carried out. The most important thing is to start planning and exploring options,” he says.

Be the first one to comment on this article.