Photo: iStock

After years of sluggish, almost negligible progress, the opening of the Vinča regional sanitary landfill was a welcome step forward on Serbia’s path to improving waste management. However, there is still a lot to be done before the country can claim to be truly managing its waste, as can be seen from the series of articles published by Balkan Green Energy News under the title “Serbia, from garbage dumps to circular economy.” Over the past year, prominent domestic and international experts have scanned in detail the state of the sector and offered recommendations – “commandments”- for tackling problems that threaten human health and the environment. The ten most important of these recommendations are presented in this article.

Waste management, much like healthcare or education, requires a country to have an appropriate system in place. In Serbia, however, the waste management system is not simply poor, but virtually non-existent. This, in a nutshell, is how the experts see the situation in Serbia at the moment, and why they believe a system must be built from scratch. That, however, would require decision-making on multiple plains: shutting down unsanitary landfills is not possible before sanitary ones have been built, and that, in turn, is not possible without a waste sorting system in place, which, again, cannot be established without a market price of waste management services, and so on and so forth.

The opening of the Vinča regional sanitary landfill, built on the site of Europe’s largest unsanitary landfill (garbage dump), has demonstrated how such moves can make a difference, but it has also exposed the severity of the problem: its operation has helped increase the total quantity of waste deposited at sanitary landfills in Serbia by 50%, from about 500,000 tons in 2020 to some 850,000 in 2021. However, about two million tons, or 70% of all generated waste, still ends up in unsanitary landfills or illegal garbage dumps every year.

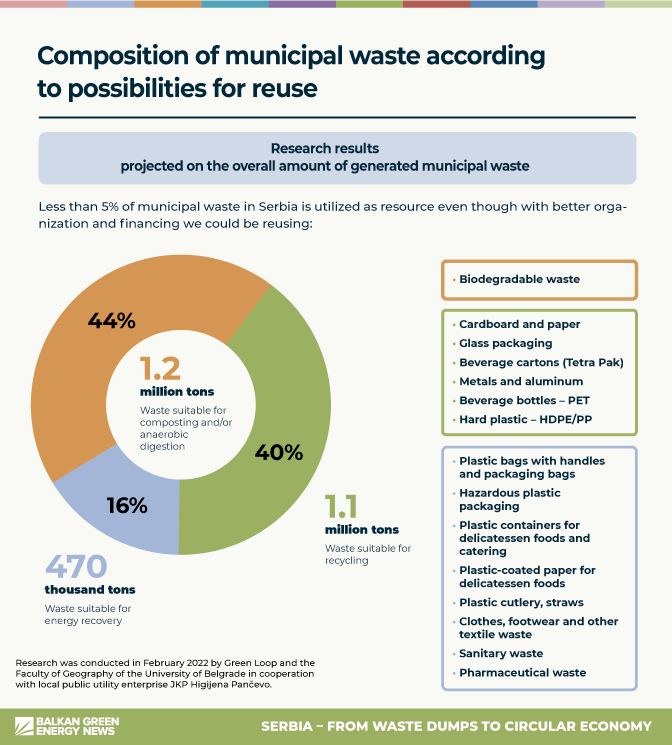

The series of texts published by Balkan Green Energy News began with the issue of municipal waste, showing beyond doubt that garbage dumps in Serbia are quietly poisoning its citizens, but also that municipal waste is Serbia’s untapped resource. An analysis of the packaging waste segment led to a conclusion that citizens pay for businesses’ irresponsibility.

The article titled Hazardous industrial waste – export is expensive, but landfilling costs even more warns of the far-reaching consequences of neglecting the issue of industrial waste due to accumulated problems.

Finally, we asked the question: Waste-to-energy in Serbia – a cause for concern or an opportunity to reap environmental-climate-energy benefits?, with the aim of encouraging dialogue on this solution, which is still controversial in Serbia due to the country’s poor track record in environmental management, but which has been widely embraced in the rest of Europe.

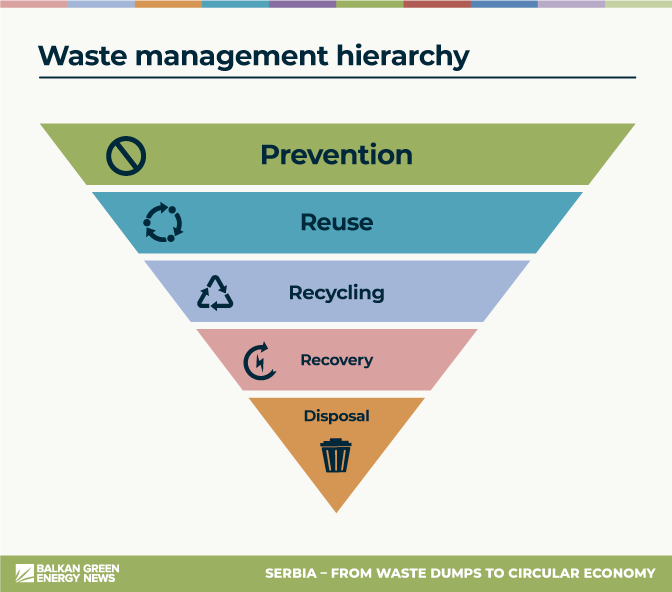

1. Respect the waste management hierarchy

The waste management system may be complex, but the waste hierarchy itself is not, and respecting this hierarchy is the first, and most essential, recommendation for establishing and operating such a system.

Instead of being treated in waste treatment facilities, Serbia’s waste ends up in nature, contaminating land, water, and air. This calls for the state to do everything in its power to enable the full application of the waste hierarchy principle, by creating a legal framework and ensuring its strict implementation as a prerequisite for a waste management system to even exist.

Instead of being treated in facilities, Serbia’s waste ends up in nature, contaminating land, water, and air

In brief, the waste management hierarchy puts disposal, or landfilling, at the bottom of the pyramid, which means that the quantities of landfilled waste must be minimized. The first step is to reduce waste generation through prevention, and the second is to enable the reuse of materials by applying circular economy principles. The third step in the hierarchy is recycling and the fourth, energy recovery from waste, or waste-to-energy.

Disposal, which is at the moment the dominant trend in waste management in Serbia, is ruled out, except when it comes to waste that cannot be dealt with in any of the previous steps.

2. Ensure waste sorting at source

If the waste hierarchy is the cornerstone of good waste management, then waste separation is its vital element. And there can be no waste separation without a developed infrastructure for sorting, collection, and transportation, which should be ensured by local utilities.

The recommendation is to establish a system of waste sorting at source, in households as well as businesses, and to separate organic from inorganic waste right away.

Waste sorting at source is essential for sustainable waste management

Without separating waste at the place where it is generated and preparing it for the next stages of management (reuse through composting, recycling, or energy recovery), it is not possible to manage waste sustainably or create new value from waste.

3. Introduce adequate prices for utility services

Good waste management has a price, and that price has to be paid by those who generate waste.

The average household in Serbia pays about EUR 5 a month for waste management services, compared with EUR 20 in Slovenia and EUR 50 in Austria.

However, the lower price of the service in Serbia is appropriate given that it only includes waste collection and transportation to landfills. This is how most waste utilities in Serbia operate, and their activities cannot be considered waste management, but plain garbage dumping.

The type of waste management seen in Slovenia and Austria involves building infrastructure that includes sanitary landfills, recycling centers, waste treatment facilities, and waste collection and separation equipment, as well as managing that infrastructure – and all that comes at a higher price.

Raising the price of the utility service would require a different billing method – charging customers by the quantity of waste collected, instead of their floor area, which would incentivize citizens and businesses to reduce the amounts of waste they generate and increase the share of waste for recycling.

4. Impose taxes to discourage landfilling

To turn waste disposal from the most preferred option in waste management in Serbia into the least preferred option, as envisaged by the waste hierarchy, and as is the case in European countries, several conditions must be met, including discouraging landfilling.

Landfilling cannot remain the cheapest option if the aim is to minimize the quantities of landfilled waste. The financial mechanisms (eco-taxes) used in the EU to make waste disposal expensive include a landfill tax, fees on products placed on the market that become waste after being used (packaging, electrical and electronic devices, oils, tires, pharmaceutical products, vehicles), and fees on unrecycled waste. The purpose of these mechanisms is not only to make landfilling more expensive, but also to raise funds to cover the costs of separate collection of waste and its treatment.

Since very few waste fractions are commercially viable for collection and treatment, it is necessary to use revenues from environmental fees to finance investment in infrastructure and cover the operational costs of collection and treatment.

Levying a landfill tax means that businesses, including landfills, pay fees calculated per ton of landfilled waste. These revenues go to the environmental protection fund and are then invested in mitigating the damage caused by landfilling or in developing a prevention system.

Given that waste in Serbia is still mostly disposed of in unsanitary landfills, it is recommended to introduce the tax gradually. Initially, it should be mandatory for businesses that dispose of waste in landfills and for utility companies that use unsanitary landfills. In the next stage, after the closure of unsanitary landfills, it would also be imposed on all sanitary landfills.

By amending the Law on fees for the use of public goods, existing packaging fees can be applied to all packaging that is not recycled or reused, which would mean that companies that place packaging on the market would be obliged to pay an environmental fee for all their packaging that does not end up in treatment facilities.

5. Educate citizens

Citizens are both part of the problem and part of the solution, and their education in this field must be continuous, systemic, and adapted to all layers of society.

Over the past years, numerous projects have been implemented in Serbia to raise awareness and educate citizens on the topic of waste and environmental protection in general, often with budgets far too big and with very modest results. This is why decision makers should think through how to organize such campaigns and who should implement them.

6. Build sanitary landfills and remove unsanitary ones

One doesn’t have to be an expert to realize that a prerequisite for introducing a sustainable waste management system is solving the issue of landfills, by building sanitary landfills and removing the unsanitary ones. Even so, given the lack of action, it may be necessary to point out some elementary and devastating data once again.

Serbia has only 12 sanitary landfills, while the number of unsanitary landfills (garbage dumps), which are prohibited in the EU, is 135. Out of the 2.9 million tons of municipal waste generated every year, as much as 85%, or about 2.5 million tons, ends up in unsanitary landfills.

Just how dangerous they are is shown in the Report on the State of the Environment in the Republic of Serbia for 2020, which identified 213 contaminated and potentially contaminated locations with the confirmed presence of hazardous and harmful substances in concentrations that can cause a significant risk to human health and the environment. Of that number, as many as 153 locations are associated with landfills.

The soil samples from those locations exceeded the limit values for cadmium, copper, zinc, nickel, chromium and cobalt, lead, strontium. These harmful substances came into the ground through leachate, which, due to the decomposition of mainly biodegradable waste, but also other types of waste, including hazardous waste, seeps out of the landfills.

Unlike sanitary landfills, unsanitary landfills do not have technical solutions for collecting and purifying the by-products of the decomposition of waste, and there is also landfill gas methane, which is 20 times as harmful to climate as CO2.

Fires are also frequent at landfills, especially during the summer months, emitting very harmful and carcinogenic substances – dioxins and furans.

7. Introduce a deposit return scheme for packaging

The issue of packaging waste management is one of the most problematic in Serbia. Between 2010 and 2020, only 39% of packaging waste was recycled, while the rest ended up uncontrolled in nature or in landfills.

Under the Law on waste management, the responsibility and duty of care for packaging waste lies with those who place it on the market, that is, businesses, but in reality more than a third of the packaging placed on the market ends up where it doesn’t belong – in nature, on the streets, in garbage dumps. This is according to official data, while unofficial data shows the figure is twice as high.

A solution is seen in introducing a fee for landfilled packaging waste in order to make landfilling the most expensive and least profitable option.

Another option is to establish a deposit return system. This has been discussed for years, but with no tangible results because, as can be heard unofficially in waste management circles, “the big ones are obstructing” the introduction of a deposit return system.

The experience of a great number of countries which have this system in place has shown that it enables the collection of over 90% of beverage packaging, while it can also help best utilize PET and glass bottles, cans, and Tetra Pak, or cardboard beverage packaging, as a resource, given they are 100% recyclable.

8. Build plants for hazardous industrial waste treatment

The lack of capacities to treat industrial waste, which includes agricultural, construction, medical, and commercial waste, increases the costs doing businesses and is one of the main reasons, along with poor inspection oversight, for its illegal disposal.

The quantities of industrial waste in Serbia are not small. There is about 300,000 tons of historic waste in the country, while a further 9.6 million tons of new industrial waste is generated every year, almost 70,000 tons of which is hazardous waste.

Currently, that waste ends up in the landfills of companies themselves, garbage dumps, or illegal dumps, but it is also exported and, probably, illegally disposed of and even burned (waste oil, plastics). Waste disposal in illegal dumps, such as garbage dumps and company landfills, is not safe and it increases the adverse impacts on human health and the environment.

Exporting industrial waste increases business costs, but also involves lengthy and complicated procedures, so it is estimated that it has cost the Serbian economy around EUR 35 million in the past nine years. Treating industrial waste in Serbia would be much cheaper, and it would employ domestic capacities.

At the same time, lower costs would incentivize businesses not to resort to illegal disposal.

9. Enable energy recovery from waste

While waste-to-energy in Serbia is still a controversial issue, it is common practice in the EU, where there are 155 plants generating energy from hazardous waste and as many as 497 using non-hazardous waste from households, industry, and the building sector.

The opportunities arising from waste-to-energy are best illustrated by the following fact: out of 2.9 million tons of municipal waste generated annually, about 500,000 tons cannot, with the available technologies, be used in any other way except for energy recovery. Serbia is already building its first waste-to-energy plant, at the newly-opened Vinča regional landfill, while several other such facilities have been announced.

Experts say building waste-to-energy plants is an option, but only as long as they comply with the highest EU standards

The experts we talked to agree that this option is acceptable, but only after waste has been handled in line with the waste hierarchy, which means reuse and recycling first. If Serbia opts for a more extensive use of waste for energy recovery, it should only be done in line with the highest European and global standards and with a strict implementation of laws and monitoring.

10. Ban oxo-degradable bags

Even though many hailed Serbia’s ban on classic plastic bags as a great victory in the fight against waste and plastics, the enthusiasm waned very quickly because the law encouraged the use of oxo-degradable bags, which are misrepresented as biodegradable.

Oxo-degradable bags are in fact regular plastic bags

These bags are in fact regular plastic bags with additives that accelerate their fragmentation into tiny pieces – microplastics. These tiny fragments do not simply vanish, but they rather reach and contaminate the soil, air, water, and even the food chain much faster than regular plastic bags.

Without any justification, oxo-degradable bags are promoted as an ecological solution by exempting their producers from environmental fees, which costs Serbia’s state budget about EUR 1 million each year. That money could be used to finance the separation of plastic bags from municipal waste and recycling.

Be the first one to comment on this article.