A strong government, working in the community interest, will have companies and the people paying their fair share to keep their environment clean, says David Newman, the outgoing president of the International Solid Waste Association (ISWA). „If the government cannot resist the pressure of big companies, then they don’t pay. Someone else does,“ he told Balkan Green Energy News in an interview before the global body’s annual congress in Novi Sad, Serbia.

Newman will pass over the presidency to Antonis Mavropolous at the event. He said he was very proud of the association’s achievements during the two mandates of a total of four years at its helm. „Six years ago, when I was vice president, the focus was that the association had to be influential because we had to raise awareness about waste as a major emergency. We had to find partnerships and alliances and to work together with people who thought that too. We’ve been extremely successful,“ he said and expressed hope ISWA will sign a memorandum of understanding with the World Bank at the forthcoming congress.

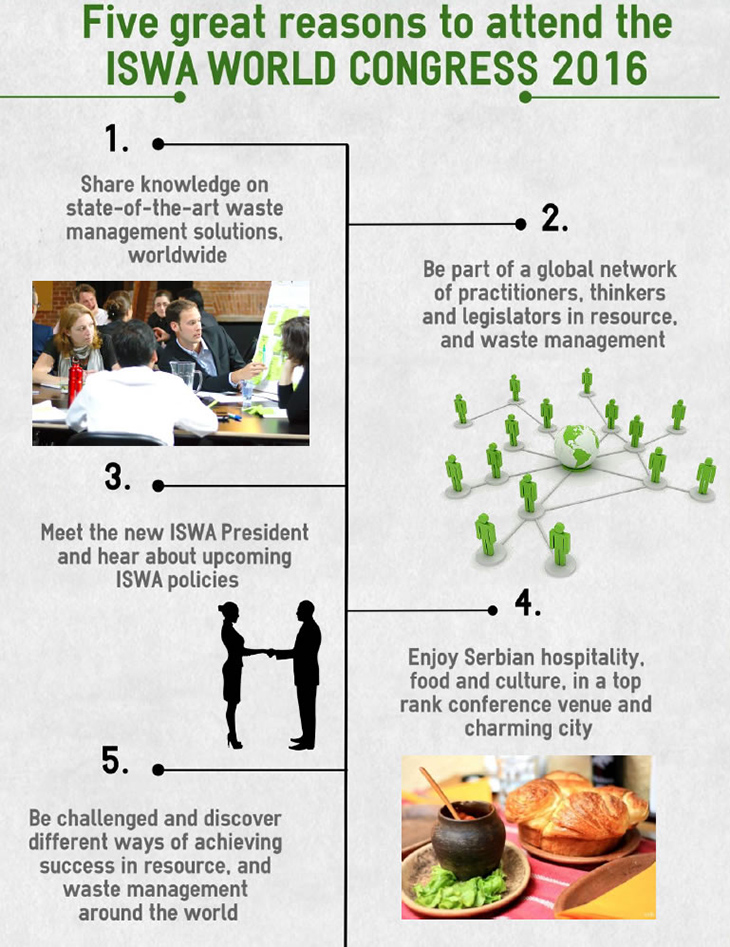

What are your other expectations for the three-day event in Serbia starting on September 19?

Countries bid every year to hold the congress and we decided upon Novi Sad, against London. You shouldn’t always do conferences at places that are famous, where everything is easy, sorted out and working perfectly. Serbia is a candidate to join the European Union and is a long way from getting its waste management system in place. The whole of Southeastern Europe is in the same situation and we strategically chose to organize the event here. We have to bring the message of good waste management, exchange experiences with local people and learn about the good things that they are doing and the problems they have.

How did the policy to make polluters pay work out in particular markets and regions around the world?

Less than 20% of waste is recycled globally, 10% is incinerated and the rest is thrown into a hole in the ground. Or a landfill, good or bad, a dump or the river, but 70% is totally untreated. Where is waste recycled and used to recover energy? In advanced economies, where we have been able to establish the concept that the polluter pays. There is very little recycling in the developing world.

Photo 1: Dumpsite Philipines

Citizens and everyone else pay to protect the environment. The European Union regulates that batteries, cars, tyres, packaging, WEEE, oil, are recycled and member countries enforce the directives sometimes badly, sometimes well. Money is coming from the producers of the materials which go into the waste stream, to collect it from there.

We have to bring to bring the message of good waste management, exchange experiences with local people and learn about the good things that they are doing and the problems they have.

Besides the EU, Australia has got some of the ’polluter pays’ responsibilities, as do a few states in the United States, Korea, Japan, while in the rest of the world there is more or less nothing! To answer your question, we’ve done a poor job.

If it was up to you personally, which are the most important and effective measures would you opt for in raising population awareness in the sector, and the penalties to get a country advance fast in waste management?

Countries like the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden and Austria are doing well simply because there is a strong government. It can make and enforce laws even if they are unpopular with certain parts of society. It is raising taxes and introducing penalties for noncompliance.

Photo 2: Waste to Energy plant Spittelau Vienna Austria

On the other hand, there are governments that are weak or have an unclear structure: the ministry is responsible for one thing, but not everything, while a city or a municipality has different or overlapping powers and so on. Then you get chaos, and we have it in 70% of the world. So sorting out the governance is fundamental.

There are governments that are weak or have an unclear structure. Then you get chaos, and we have it in 70% of the world.

Are there hacks at all for general inertia in the developing world? Are you aware of examples of progress and good practice?

Malaysia took a long time to get its system sorted out. After 15 years of negotiations with all stakeholders, a few years ago a decision was made and the country finally gave contracts for up to 20 years to private companies to keep the streets clean, take waste to sanitary landfills and build incinerators. The country is on the right road, while neighbouring Indonesia, otherwise very rich in resources, is in a mess with dumping and burning material everywhere.

Chile is possibly the best example of progress made in Latin America. Mexico is also doing significantly well. Even though Africa has difficulties everywhere in general, Rwanda is extremely clean and handles its waste reasonably well, while in neighbouring Tanzania and Kenya there are open dumps everywhere.

Southeastern Europe is a place with a large chunk of people barely making ends meet. Traditionally, inhabitants are aware a lot of the poverty comes from squandering and also from pollution, but it seems recycling was persistently seen as taboo. There are population groups which manage solid waste for a living, though predominantly in a primitive manner and with physical risk, and the activity is looked down upon. Can we reconcile the two extremes?

In comparison to times which I also remember, when very little waste was created or thrown away, while dustmen came only once a week, it happens that your country switches to a free market economy in which everybody is buying everything but public services haven’t yet got the structure to handle all that. There’s an inevitable time lapse between the two.

People from the informal sector that some call scavengers make a dollar or two a day picking waste. That’s close to slavery, while it’s the only recycling in 70% of the world! You can only raise the level up the chain. That means you have to have financial resources to do the rest properly. It comes back to what I said about governance. It’s making sure the people who put waste to the market also pay for it and take responsibility. Imagine if those who sell Coca-Cola bottles or chocolate bars offer (say) EUR 100 million per year in a Balkan country to recover the plastic and the packaging. It would stimulate the whole economy. Your scavenging sector wouldn’t find such waste in dumpsters anymore, but those people can be brought in as collectors, this time in properly managed plants.

Imagine if those who sell Coca-Cola bottles or chocolate bars offer (say) EUR 100 million per year in a Balkan country to recover the plastic and the packaging.

However, you have to have the money to do this. My principle is that everybody produces waste and that everybody needs to pay for a cleaner environment, even if they can afford only USD 5 per year. Unilever, Procter and Gamble, Apple with its iPhones, or Hewlett-Packard with its computers, they all must pay to get the materials recovered.

That’s how you make the transition. It’s inevitable and don’t beat yourselves about it. It takes time, it took us 30 to 40 years in Western Europe to sort it out.

Is solid waste more beneficial as biomass fuel or as a commodity for recycling in an economy, a society and for the environment? What are the differences depending on the material and on the availability of a resource in particular regions?

I’m a practical person, not an ideologist. I think what works is good. But what works in one place may not work somewhere else. In Northern Europe there are huge incinerators burning away 365 days a year. Those countries are cold nine months out of 12 and their burning waste is not just providing electricity but also hot water for district heating. On the other hand, that’s no solution for Cairo or Athens.

In Africa, 70% or 80% is wet food or vegetation. Burning water is very expensive and the technology won’t work there. Countries like Denmark or Sweden don’t have oil and gas fields for energy and they are probably better off maximizing what it can get out of incineration of waste rather than the material itself.

The recycling and gathering sector is set to significantly develop in Southeastern Europe, as technology and legislation improve to bring higher yield from the activity. What are your experiences with the ratio of the demand for experts in the field and the number of professionals with quality education in the labour market?

Firstly, ISWA does a waste management certificate programme, which is particularly popular in some Southeast Asian countries and Latin America. We recently established training centers in Malaysia in Oman. We have a winter school in Texas. Thousands and thousands of people are going into environmental and waste management studies. There’s no shortage of talented young people coming out of those courses. Actually, the University of Novi Sad has a very good training center for waste management.

Photo 3: Young professionals in waste management

But there are several concepts. At a very basic level of picking it up off the streets and trucking it to a landfill, you don’t need to be a nuclear scientist to understand it. You just need to be able to organize it. Some of the biggest waste companies were founded by people who were truck drivers. It was literally about logistics.

And what are ISWA’s ties with educational institutions and associations in Southeastern Europe? What activities are the most important?

We did a summer school in Romania. We cooperate with waste associations which are in development in Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. We will be building up some educational programs with them. We already do a series of eight to ten seminars and conferences in Southeastern Europe every year, with fifty or up to 200 people attending each one. Let’s hope we can do more!