Photo: iStock

It was in late 2016 and early 2017, when some 1,500 tons of industrial waste was discovered illegally buried or stored inside abandoned factories, that the public in Serbia first got acquainted with this type of waste. Industrial waste is far from harmless, since a good part of it is hazardous to the environment as well as people. Even though more than five years have passed, and despite the media pomp at the time and promises by the then environment minister that the state would tackle the problem, the issue of industrial waste management remains unresolved. As is the case with other types of waste, industrial waste is waiting for some new people to address the problems.

The industrial waste discovered in Bela Crkva, Obrenovac, Novi Sad, Pančevo and Bavanište was historic waste from bankrupt socially-owned firms, but also waste from active businesses which, for the lack of inspection oversight, had been illegally buried or disposed, instead of being properly managed.

Irregularities in industrial waste management, which, legally speaking, may well be described as criminal offences, are due to the fact that exporting waste is far too expensive for businesses, in the absence of adequate recycling or waste-to-energy facilities in Serbia.

Illegal waste disposal will continue until Serbia develops recycling and waste-to-energy capacities and strengthens inspection oversight, given that waste cannot just go away.

Nearly 70,000 tons of hazardous waste is generated in Serbia every year

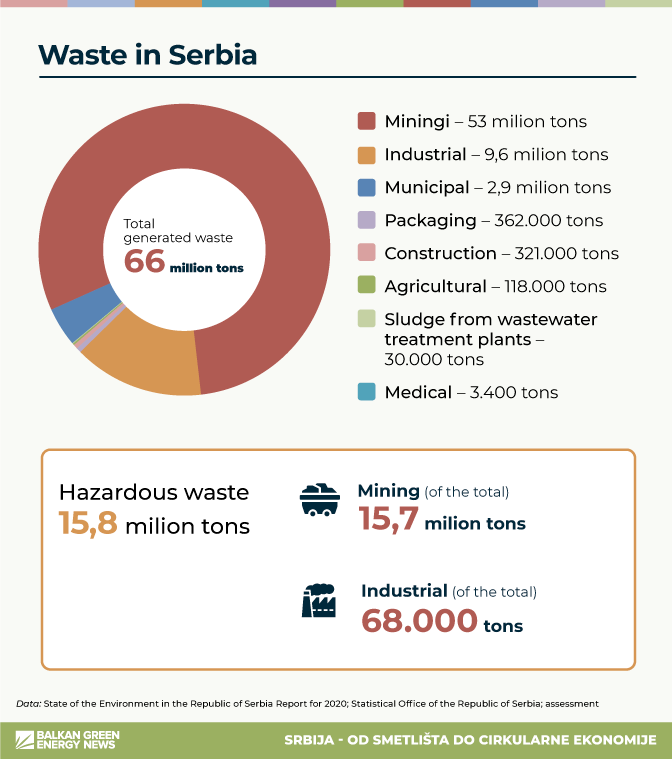

The quantities of industrial waste generated in Serbia are considerable. There is some 300,000 tons of industrial waste in the country, and a further 9.6 million tons is generated every year, of which 70,000 tons is hazardous.

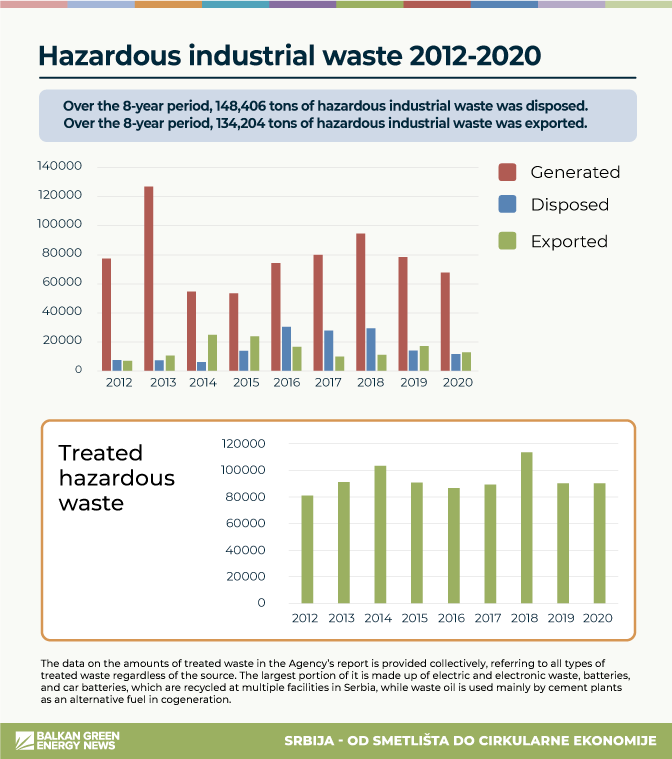

According to a report on waste management in Serbia for the period 2011-2020, produced by the Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA), nearly 150,000 tons of hazardous waste was landfilled between 2012 and 2020, or 21% of all generated hazardous waste, while 19% was exported.

At an average price of export and treatment abroad of EUR 2.5 per kilogram (a conservative estimate), the disposal of hazardous waste abroad cost Serbian businesses some EUR 35 million in the 9-year period, or about EUR 4 million a year. The true cost of waste disposal at legal and illegal dumps is not known, given that the price of such practices is paid and will continue to be paid with the health of citizens and the environment.

Siniša Mitrović and Marko Rokvić (Photo: Balkan Green Energy News)

As is the case with municipal and packaging waste, Serbia lacks an effective system for the management of other types of waste, which can be described collectively as industrial waste and which includes agricultural, construction, and medical waste, sludge from wastewater treatment plants, and commercial waste (from businesses and institutions whose activities include trade, services, office work, sport, recreation, or entertainment).

In this latest article in the series “Serbia, from garbage dumps to circular economy,” we discuss the flow of industrial waste, primarily hazardous waste, with Marko Rokvić, CEO of Green Group, and Siniša Mitrović, director of the Center for Circular Economy at the Chamber Of Commerce and Industry of Serbia (PKS).

Industrial waste – the buried hazard

Industrial waste includes all types of waste generated in industrial production, from packaging for raw materials (cardboard, nylon, wood pallets, barrels) to waste generated in production processes, various leftovers, mixed raw materials, waste resulting from accidents or cleaning, as well as waste from equipment maintenance…

Agricultural waste, for instance, includes all types of waste generated in agricultural operations, from various kinds of biowaste to plant protection products and their packaging, protective foil for crops, and machinery maintenance waste.

Packaging that contained hazardous waste is also hazardous waste

Industrial waste is in the spotlight because it contains hazardous waste. Hazardous waste is defined as waste whose origin, composition, and concentration of hazardous substances make it capable of having a harmful effect on the environment or human health and which has at least one of the hazardous properties determined by special regulations. Hazardous waste also includes packaging in which hazardous waste was or is kept.

“Hazardous waste comes from the chemical, textile, pharmaceutical, and leather industries, from the manufacture of electrical or electronic equipment, batteries, car batteries, paints, from electrolysis and plastics. Such waste also includes used oil, contaminated packaging, oily rags, waste paints, waste filters, oily water,” says Marko Rokvić, CEO of Green Group.

Non-hazardous waste includes mostly cardboard, various types of plastics, and metals, and it often has a market value so most businesses do manage it.

Historic waste is particularly problematic since its disposal is incredibly difficult and expensive, because it is stored in abandoned factories, reservoirs, warehouses, according to him.

In such locations, caution is of utmost importance as one never knows what kind of waste, and in which quantities and condition, will be found there, he says. Covering the costs of disposing of such waste is the responsibility of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, according to him.

The waste discovered in Bela Crkva (several hundred tons), Obrenovac (over 50 tons), Novi Sad (around 1,000 tons), near Pančevo and Bavanište (around 100 tons) is partly historic waste. Even though the waste has now been removed from all these locations, no analysis has been conducted yet to determine the level of pollution in the soil.

Cleaning up the historic waste requires RSD 10 billion

The long and inadequate storing of this industrial waste had undoubtedly caused pollution to the soil and groundwater. This is why its disposal must include the decontamination and reclamation of the locations where it was discovered, according to Siniša Mitrović, director of the Center for Circular Economy at the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Serbia (PKS).

According to him, environmental inspectors have ordered the waste to be categorized, temporarily stored in a safe manner, and then handed over to waste management operators for treatment, but to no avail.

Many of the firms have not even stored their waste temporarily in a safe manner.

“That’s why the state urgently needs to help dispose of the waste from those locations. The ministry’s engagement is commendable, and we propose that RSD 1 billion be set aside each year over the next ten years to clean up those locations. However, even that will not be enough unless we invest in the domestic infrastructure for storing and treatment,” says Mitrović.

Sludge from wastewater plants will be Serbia’s next challenge

Serbia will soon face another challenge in waste management, namely increasing quantities of sewage sludge from wastewater treatment plants. In the coming years, the country plans to invest some EUR 4 billion in such plants and sewage infrastructure.

Serbia currently generates around 30,000 tons of sewage sludge a year, but the figure is set to rise to 500,000 tons when all the planned facilities are built. Experts say there is no legal way to safely manage this type of waste in Serbia today.

There has been no integrated approach in the legislation, and the issue has reached stalemate – the law does not allow sending waste with over 5% of organic matter, such as sewage sludge, to sanitary landfills, while its disposal on regular land is also forbidden.

Experts warn against imposing bad solutions from other countries and propose treating sludge as a separate category of waste

Eventually, sewage sludge ends up at garbage dumps or local disposal sites, or is exported. If not treated as hazardous waste, sludge can be dangerous, since it contains heavy metals, but also polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), micro plastics, drug residues, and organic pollutants (pathogenic microorganisms).

At a recent roundtable held at Belgrade’s Faculty of Technology and Metallurgy, experts warned against imposing bad solutions from other countries and proposed treating sewage sludge as a separate category of waste, by adopting a government decree or a rulebook.

About 43% of sewage sludge in the EU is used in agriculture

According to Eurostat’s data for 2015, about 21% of all sewage sludge in the European Union (EU) was used for energy recovery through cogeneration, incineration, and mono-incineration – combustion together with other wastes or alone in special facilities, which is the most common type of sludge treatment in Germany. The development of phosphorus recovery technologies enabled pure phosphorus to be obtained from ash, and then be used in the production of fertilizers, increasing the percentage of sewage sludge used in agriculture from 28% in 2005 to 43% in 2015.

The composting rate is also on the rise, but only for sludge that does not contain heavy metals and other harmful substances. Due to lack of treatment facilities and the high price of treatment, around 17% of the EU’s sludge still ends up in landfills, even though the landfilling of sludge is prohibited by law in a large number of member states.

About 25% of businesses in Serbia do not report hazardous waste

Under the Law on waste management, each firm is required to separate all kinds of waste it generates, store it safely, and hand it over to a licensed waste management operator for storing, treatment, or export. The operator can be a recycling firm, a waste treatment plant, or a facility for the storing of waste intended for export.

Marko Rokvić says there are more or less enough operators in Serbia to handle useful waste, including large recyclers and small local waste collectors. Even the existing capacities for cardboard, PET, and metal recycling far exceed the amounts collected in Serbia (from businesses and citizens).

Hazardous waste is handled by operators with special licenses, either for storing or for treatment.

About a quarter of hazardous waste gets dumped or buried somewhere in Serbia

Talking about the problems in waste management in Serbia, Rokvić says that many businesses in Serbia manage their waste well, but that at least 25% do not report the waste they generate. That waste, he says, gets dumped or buried somewhere in Serbia.

Even though the Law is clear, the enforcement mechanism and inspections are inefficient, according to him.

Another problem is insufficient capacities for storing and treatment, which causes delays in collecting waste from businesses for storing, treatment, or export, according to him.

The existing capacities for storing and treatment are insufficient

There are certain physical-chemical treatments where hazardous waste is rendered inert using various chemical agents. Contaminated packaging is also treated, and waste oil is refined or co-incinerated. Also undergoing treatment is chemical waste whose properties and composition allow for it to be treated with existing technologies.

This is why about 80% of the 70,000 tons of hazardous waste is exported every year to European countries, mostly to Austria, but also Germany, Switzerland, and Greece. That waste is mainly sent to incineration plants, which use it as fuel.

Certain operators charge firms for managing their waste, but then bury it somewhere instead

Waste export is a very complex process, and expensive too, he says. The costs of collection are covered by those who generate the waste, and they pay fees ranging from EUR 0.5 per kilogram for some types of waste that can be treated in Serbia to EUR 5 per kilogram for waste that is exported.

Another problem is operators who break the law, taking money from businesses to take care of their waste and then burying it somewhere instead, as was the case in Obrenovac, or storing it inside abandoned factories, as they did in Bela Crkva.

Nevertheless, the overall situation with hazardous waste in Serbia is better than it was some ten years ago, when all waste ended up at local landfills, according to him.

Hazardous waste treatment in Serbia would bring savings to businesses

Siniša Mitrović of the PKS says that Serbia lacks strategic facilities for the management of hazardous waste, while the government’s plans to build such plants were met with strong public resistance.

This is the reason why Serbia did not get the EUR 14 million the EU had approved for the construction of a facility for the physical-chemical treatment of waste, according to Mitrović.

Such a facility was envisaged in the waste management strategy for the period 2010-2019, which included developing a hazardous waste management system, building regional storing facilities, and launching construction on a facility for the physical-chemical treatment of waste by 2014.

Mitrović: a competitive price of treatment in Serbia would put a stop to waste export and reduce business costs

Elixir Group’s investment in the Western Balkans’ first incinerator for industrial waste, with a capacity of 80,000 tons, could help solve the problem of historic waste in Serbia as well as waste generated in industrial production, according to Mitrović.

Without infrastructure for industrial and hazardous waste management, there can be no GDP growth, new investments, or sustainable production, he says, adding that a competitive price of treatment in Serbia would put a stop to waste export and increase the competitiveness of Serbia’s economy by lowering business costs.

Marko Rokvić, CEO of Green Group, believes the waste management hierarchy is rarely applied in Serbia. Companies, according to him, put their product first, as well as the price and quality, while dealing with waste only to the extent that they are forced by the state.

Rokvić: hazardous waste is our reality and it cannot be escaped

He agrees that Elixir Group’s investment in the waste incinerator could be a good solution for Serbia, especially in terms of addressing the storing problems, limited treatment of hazardous waste, and export. Such facilities, if built in line with global standards, are quite costly, and no operator has so far been able to carry out such a project.

Rokvić believes that the state should support such projects, but that it should not get involved financially.

He recalls that the government has attempted to launch hazardous waste management centers, but that such plans have fallen through due to public resistance.

“People get really scared when they hear the term ‘hazardous waste’ even though they don’t know much about it. Given our experience, it doesn’t surprise me that people have reservations about such projects,” he says.

Rokvić stresses that hazardous waste is a reality that cannot be escaped, and that the “not-in-my-backyard” principle cannot always be applied.

“We must be aware how much of it there is, and act as responsible people who take responsibility for their actions,” said Rokvić, noting that former president of the International Solid Waste Association (ISWA) Antonis Mavropoulos said that “it’s about people, not waste.”

GOOD TO KNOW

HAZARDOUS WASTE – waste that displays at least one of the properties that make it hazardous (explosiveness, flammability, tendency to oxidation, acute toxicity, infectivity, corrosiveness, is an organic peroxide, releases flammable gases in contact with air, releases toxic substances in contact with air or water, contains toxic substances with delayed chronic effects, has ecotoxic properties), as well as packaging in which hazardous waste was or is kept.

NON-HAZARDOUS WASTE – waste that has no properties of hazardous waste.

INDUSTRIAL WASTE – waste generated in industrial production, from packaging for raw materials (cardboard, nylon, wood pallets, barrels) to waste generated in production processes, various leftovers, mixed raw materials, waste resulting from accidents or cleaning, as well as waste from equipment maintenance… (Serbia’s Law on waste management does not classify mining or quarry waste as hazardous waste).

WASTE TREATMENT – re-use or disposal operations, including preparation for re-use or disposal.

WASTE-TO-ENERGY FACILITIES; WASTE INCINERATORS – facilities for the thermal treatment of waste (combustion). There are two types of treatment: incineration and co-incineration.

WASTE INCINERATION (BURNING) – thermal treatment with or without energy recovery, which includes gasification, pyrolysis, and plasma combustion.

CO-INCINERATION; ENERGY RECOVERY FROM WASTE – thermal treatment of waste with the primary purpose of producing energy or solid products where waste is used as main or auxiliary fuel or in which waste is burnt for the purpose of disposal.

Most of the toxic waste is from mining activity – historic and current. Our company has a proven technology that can permanently ‘bind’ dissolved heavy metals ‘in situ’.

Our partners are then able to re-vegetate the mine tailings with a high yield energy crop that is best used to sequester carbon and utilise the vegetation to add nutrients to the treated tailings.

Which law does not allow the deposit of sewage sludge in licensed landfill sites in Serbia