Photo: iStock

There is an explosion of interest in private power purchase agreements (PPAs) in the Balkans and a myriad of options are available, Finance in Motion Investment Manager Matti Piiparinen said. Together with the Green for Growth Fund (GGF), which it advises, and international law firm Simmons & Simmons, the company held an online workshop with power project developers and discussed common questions about the concept. Developers have the choice between private or state-backed PPAs, and physical or virtual contracts, which both have their pros and cons.

Advised by Finance in Motion, the Green for Growth Fund’s technical assistance facility sponsored an online workshop led by Simmons & Simmons, called Renewable Energy Private Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). The workshop summarized key investor considerations to support successful negotiations with offtakers, resulting in bankable PPAs.

The event covered forms of renewable energy procurement and sales, types of PPAs, their market and structure, renewable energy certificates and an overview of the situation in the Balkans. It can be viewed online here.

PPAs for renewables are relatively new in much of Southeastern Europe in general, while corporate or other private agreements are only beginning to emerge. In this article, you will get valuable insight into the basics of the concept, with key terms explained.

Explosion of interest across Balkans

There is a myriad of options available to developers, Finance in Motion Investment Manager Matti Piiparinen said. The presentation focused on private PPAs for grid-connected off-site power plants.

“Utility PPAs remain available, but not necessarily in the same form as in the good old days, when you would have ministerial guarantees, hard currency, change-of-law protection, and termination payments that would cover both debt and equity returns. For instance, how a sponsor should decide between executing a 15-year contract-for-difference arrangement with an unrated state-owned utility or a short-term contract with a highly rated trader,” Finance in Motion explained.

PPAs come at a cost, but they secure price and revenue stability

Elaborating more on the context of the workshop, Finance in Motion pointed out that the Energy Community has been promoting wholesale energy markets as a way of improving integrity and transparency. While PPAs are generally limited to more liquid Western European markets, there is now “an explosion of interest across the Balkans,” Piiparinen stressed.

Emerging markets struggling to attract investments in decarbonization

The mission of the Green for Growth Fund (GGF), a public-private partnership, is to mitigate climate change and promote sustainable economic growth, primarily by investing in the reduction of energy consumption, resource use and CO2 emissions.

Typically, GGF provides debt, but it has a flexible mandate. One example is the Bogoslovec wind park in North Macedonia, where the fund provided the missing piece of equity.

GGF’s blended finance structure allows it to increase investment volumes in regions and sectors that don’t normally attract the necessary flows.

GGF normally provides loans, but there is also the possibility of equity investments, like in the Bogoslovec wind power project in North Macedonia

Finance in Motion initiates, manages and advises private debt and private equity funds in emerging markets. Its goal is to contribute to positive environmental and social impact.

“A country may be considered vulnerable due to its physical exposure to climate change, the sectoral composition of its economy or its adaptive capacity. Furthermore, emerging markets struggle to attract capital necessary to transition to net zero emissions,” according to the company.

Founded in 2009, Finance in Motion has invested EUR 8.6 billion through its funds in 40 countries. The firm currently manages EUR 3.9 billion in assets across nine funds.

PPA is critical mitigant against volatility

Marc Fèvre, a partner at Simmons & Simmons, laid out the technical aspects, legal framework and risks in the PPA realm for participants in the workshop. Alex Blomfield, another partner at Simmons & Simmons, focused on key features of earning revenue for renewable energy projects for each jurisdiction in the Western Balkans, drawing on input from regional law firm partners BDK Advokati, Dimitrijević & Partners, Divjak Topić Bahtijarević & Krka Georgi Dimitrov Attorneys, and Kalo & Associates.

The international law firm distilled the key messages and key bankability criteria from many agreements. Simmons & Simmons’ experts provide legal advice primarily to commercial and corporate clients, banks, asset managers and funds. The core sectors are energy, natural resources and infrastructure. Simmons & Simmons operates in Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

A PPA offers a hedge against electricity price risk both for the consumer and the seller

It works with developers, sponsors and lenders on the development, construction, operation, financing, and acquisition and disposal of renewable energy, energy storage and other energy transition projects. The firm frequently advises developers on their first direct PPAs, helping to ensure that risk allocation remains balanced.

“A PPA is a mitigant against volatility, but at a price, as one party is effectively taking away the market risk from the other party in return for other benefits. For example, a power developer will frequently give up the ability to benefit from increases in future market prices in return for stable revenues throughout the term of the PPA while the buyer will reduce its exposure to high market prices in return for providing the developer with protection from low prices,” Fèvre stressed.

In other words, a PPA offers a hedge against electricity price risk both for the consumer and the seller. Hedging is the reduction of a project’s exposure to market price volatility. By increasing the bankability of a project with a PPA, sponsors benefit from higher leverage, which offsets lost market-based revenue.

State-backed versus private PPAs

A government department, ministry or a state-owned utility company are the usual counterparties in a state-backed PPA. Such contracts are typically bankable as government guarantees lower credit risk, and utilities are generally expected to have longer lives than corporates.

Examples of state-owned utility PPAs are the feed-in tariff contracts that Serbia’s state-owned utility Elektroprivreda Srbije (EPS) has signed with projects which entered the 400 MW feed-in tariff quota for wind, including Kovačica, Čibuk 1 and Alibunar.

Private PPAs are like any other commercial contracts between two commercial entities. They are negotiated between a seller (generator) and an offtaker such as a corporate buyer or a utility. There is still no universal standard for the numerous models and types of contracts that are being developed.

The term private PPA is more suitable than corporate PPA as there is now “a whole universe of different sorts of buyers that participate in the PPA market,” Fèvre underscored. In addition to electricity consumers, electricity traders provide products akin to PPAs.

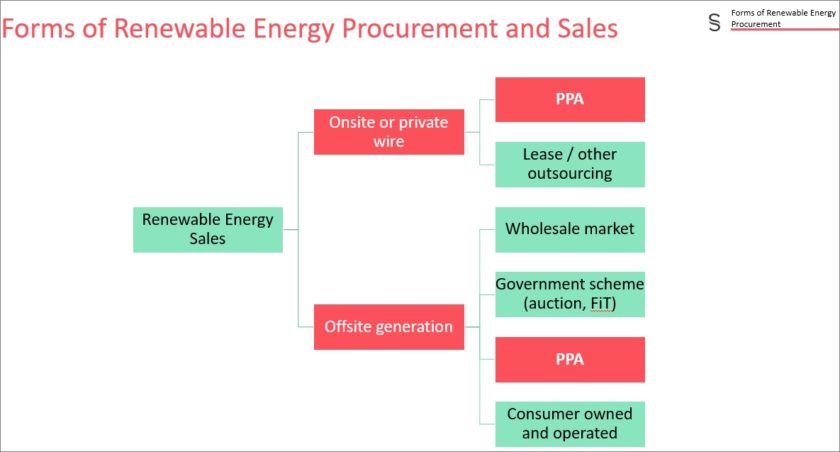

Forms of renewable energy procurement, sales

A project company can generate electricity for the client directly: at the point of consumption – onsite, or through a private wire connection. It would be referred to as an inside-the-fence arrangement.

In these cases, the energy consumer (offtaker) may outsource the construction and management of the electricity infrastructure to a third party, and remain concentrated on its own core business; it doesn’t participate in the electricity market. Such an arrangement usually covers only a portion of the consumer’s demand.

Alternatively, with offsite power plants, there are some options for selling the electricity aside from a PPA. Working through the wholesale market implies risks. It is attractive when power prices jump, but revenue may be unpredictable.

Another version is a government scheme. Auction schemes with guaranteed tariffs, such as in Serbia and Albania, are now more common than feed-in tariffs. The off-site option enables large-scale projects to cover the majority of consumption of one or more customers.

Physical versus virtual PPAs

A PPA for a renewable energy project will typically be structured under a physical or virtual (vPPA) arrangement.

In a physical PPA, the generator delivers and the buyer receives the power physically in the same grid, although not necessarily at the same delivery point. The supply goes through a private wire – behind the meter, or through a grid connection, which is arranged with a sleeved power purchase agreement.

The latter version requires using the power grid and, typically, the involvement of a utility or an energy retailer for balancing and sleeving services. The utility receives a fee for providing the service.

Virtual-financial PPA

The alternative contracting structure for private PPAs, based on the transfer of guarantees of origin, is a virtual or financial PPA.

“In a sense, it’s not a power purchase agreement. It is two separate arrangements. On one side, a power plant is generating and supplying into the local electricity market in the same way as if there were no PPA. On the other side, the buyer purchases electricity on the local market,” Fèvre commented.

The buyer doesn’t provide support to the producer like in a subsidy scheme except, for instance, a fixed price or contract for difference (CfD). If the market price is below the fixed price, the buyer pays the project the difference. But if the market price is above the fixed price, the project pays the counterparty the difference. The seller of electricity gets a stable revenue, at the agreed price.

Last year’s market premium auction in Serbia uses this structure: it envisages a 15-year contract for difference with state-owned utility company EPS, without physical offtake. Winners of the auction – the Vetrozelena, Pupin and Čibuk 2 wind farms, then proceeded to negotiate and execute, on a purely commercial basis and outside of the support mechanism, a long-term route-to-market PPA with the same state-owned utility, for a price tied to the day-ahead price on Serbian power exchange SEEPEX, with balancing services included.

In addition, also in Serbia, the recent project financing of the Krivača wind farm was based on a combination of a long-term financial PPA with a foreign electricity trader, Axpo, providing price stability, and a long-term physical PPA with a local trader enabling physical delivery of electricity from the wind farm into the grid.

Renewable energy certificates

Both physical and financial PPAs may include the sale and transfer of renewable energy certificates. In Europe, they are defined as guarantees of origin (GOs). They are trackable (by project and source), and can be traded independently from the underlying electricity.

Once retired, a GO can be used to claim the usage of that specific megawatt-hour of renewable energy. GOs already exist in a number of countries in the Western Balkans and implementation is currently under way of a scheme that will enable GOs to be traded across the region.

Be the first one to comment on this article.